JJ Collier is the only art teacher in the Grant School District, and just saw her hours reduced. (Yellow Sage Photography)

Off Target

How the managers of Oregon's $100 billion pension fund ignored expert guidance and lost big.

By James Neff

August 5, 2025

Earlier this year, Grant School District Superintendent Mark Witty faced a $900,000 hike in what his district needs to pay this coming year to the Oregon Public Employees Retirement Fund.

It was a crippling announcement. The cause of the increase? Lousy investment returns by the state agency empowered to invest public employees’ money. And when investment returns are poor, the state has to fund pension obligations by forcing local governments to make up the difference.

“We had to make significant cuts,” said Witty, whose small district educates 470 kids in grades K–12. “It’s been traumatic for people.”

He had to fire a secretary and an administrator. He couldn’t replace three teachers who were leaving, including one in special ed, as well as two teacher’s aides. He made cuts to high school vocational agriculture, sliced $20,000 from the athletics department, and cut the district’s only art teacher to half time.

That art teacher, JJ Collier, has worked at Grant Union, the combined junior and senior high school in John Day, for 19 years. At 68, she still needed more full-time years of credit for retirement. “It’s frustrating,” she says. “I was angry.”

Hard choices like those the Grant County district had to make have played out across the state’s 197 school districts as school boards and superintendents look for an estimated $670 million more over two years to pay for the increased pension fund assessments. Money that could pay for about 6,700 beginning teachers.

The pain, of course, goes far beyond school districts. Every public employer from the state of Oregon down to the smallest special district—904 government employers in all—is in materially worse shape this year because of the pension fund’s anemic investment returns.

That means fewer teachers, firefighters, nurses and other vital employees.

An OJP investigation of the Oregon Investment Council, interviews with people in and outside of the State Treasury, and an examination of thousands of pages of documents, meeting minutes and financial data show that those poor returns could have been averted if Oregon had simply invested the funds in accordance with the guidance for which it pays its outside experts handsomely.

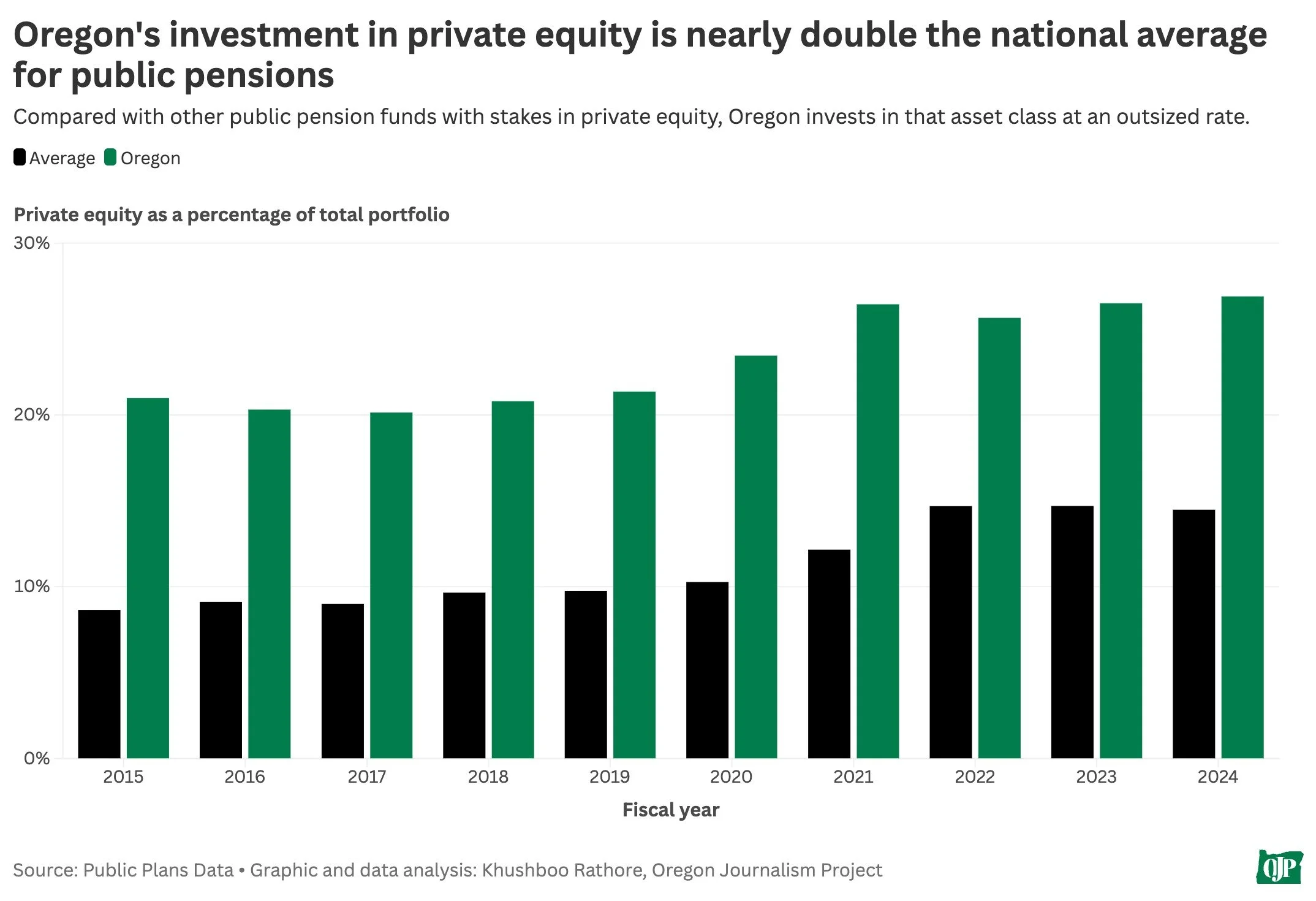

For years, that advice has been for the state to put more money in the stock market and less in a form of investment called private equity—a risky kind of financial engineering in which investment managers buy private companies and seek to resell them in seven to 10 years. And while some major state pension funds and university endowments have been reducing their private equity holdings, Oregon has stayed the course.

Results have been dismal.

For the past 10 years, Oregon’s investments in private equity yielded returns below its yardstick—the Russell 3000 Index plus 3%. Last year, Oregon’s private equity portfolio yielded just 4.1%, far below the Russell 3000 benchmark, which yielded 38.4%.

Rex Kim, the treasury’s chief investment officer since 2020, oversees the $100 billion in the pension fund and how it is invested. (Kim’s salary—$810,030—makes him the highest-paid state employee.)

He brushes off criticism of the state’s private equity portfolio, saying it’s myopic. “I'm not a big fan of taking single-period snapshots of performance.” He says his team invests for the long term, over decades of market cycles that he says show private equity beats the stock market.

Rick Pope, a retired Portland lawyer who has spent years attending OIC meetings and publishing reports about the fund for Divest Oregon, is blunt. “They have a car crash on their hands, which [his] staff continues to deny as a problem,” Pope says.

Treasury staffers, he adds, have “allocated way beyond their policy to private equity, which has damaged [Public Employee Retirement System] returns. They missed the big stock market uptick because the treasury had to sell stock market investments to fund benefits.”

Veteran reporter Ted Sickinger recently dug into these topics at The Oregonian.

Rightly so. Think of Oregon’s pension fund as a savings account on which 415,000 people rely for PERS benefits. Though most Oregonians don’t have a public pension, the success of the fund impacts their quality of life and their families’ futures.

“We should all care about PERS because this system touches just about every public service in Oregon,” says John Tapogna, senior adviser with ECOnorthwest.

Kim’s not the only one responsible. The state treasurer, who is Kim’s boss, and the other four voting members of the OIC, appointed by the governor for their investment expertise, have presided as Kim and his team have overinvested in private equity.

One of the nation’s leading experts on pension fund investing, Richard Ennis, who reviewed Oregon’s 10-year performance, recently gave OJP a withering assessment.

“Oregon has underperformed its private equity benchmark by a significant margin,” says Ennis, who helped create the field of institutional investment consulting. “They appear to be after the highest-returning asset without respect to risk-return considerations and without regard to their seeming lack of selection skill.”

Gov. Tina Kotek and lawmakers have been debating for the past six months whether Oregon schools need more funding or greater accountability for the money they spend. OJP’s reporting shows this would be far less of an issue if the state simply invested more wisely.

Poor investment returns at the State Treasury placed Grant School District Superintendent Mark Witty in a bind. (Courtesy of Grant School District)

Rex Kim, the treasury’s chief investment officer, is responsible for the portfolio’s returns. (Courtesy of Oregon.gov)

The Oregon Public Employees Retirement Fund is responsible for paying pensions to 166,000 retirees and 249,000 future retirees. To do that, PERS charges each city, county, school district and public employer 27 cents on top of every payroll dollar—the system’s highest rate ever—and gives the money to OPERF to invest. The fund uses investment gains to pay pensioners.

Investment returns—profits on the investments managers make—fuel the system.

The investment decisions treasury investment staff makes, following OIC policy, are crucial. Sometimes stocks are better than bonds. In other years, real estate or private equity might outperform.

Drawing on the expertise of highly paid outside consultants and the council, Kim’s team essentially creates a recipe for what percentage of the fund, called a target, to allocate to different asset classes: stocks, bonds, real estate and private equity, all with an eye for growth and stability that looks decades into the future.

But as any cook can tell you, too much of one ingredient and too little of another can ruin the dish.

How the fund got out of whack can be laid at the feet of the Oregon State Treasurer’s Office, its chief investment officer, and the Oregon Investment Council, a board of directors, if you will, that includes as voting members the state treasurer and four members who are appointed to the voluntary position by the governor. Understanding how these partners work together is key.

To guide its choices, treasury staff hires outside experts who tap mountains of research and the best investment analysts to formulate an investment strategy—i.e., how much of the portfolio to allocate to the various ingredients.

The state paid one of those consultants, Meketa Investment Group, $1 million in the past year for advice on the best mix.

“Asset allocation is the most important decision the OIC makes,” Meketa tells the council in its regular reports.

Records show the treasury has not followed that high-priced advice for years. For instance, Meketa’s current target for stocks is 27.5%. But just 18% of Oregon’s $100 billion pension fund is currently invested in stocks.

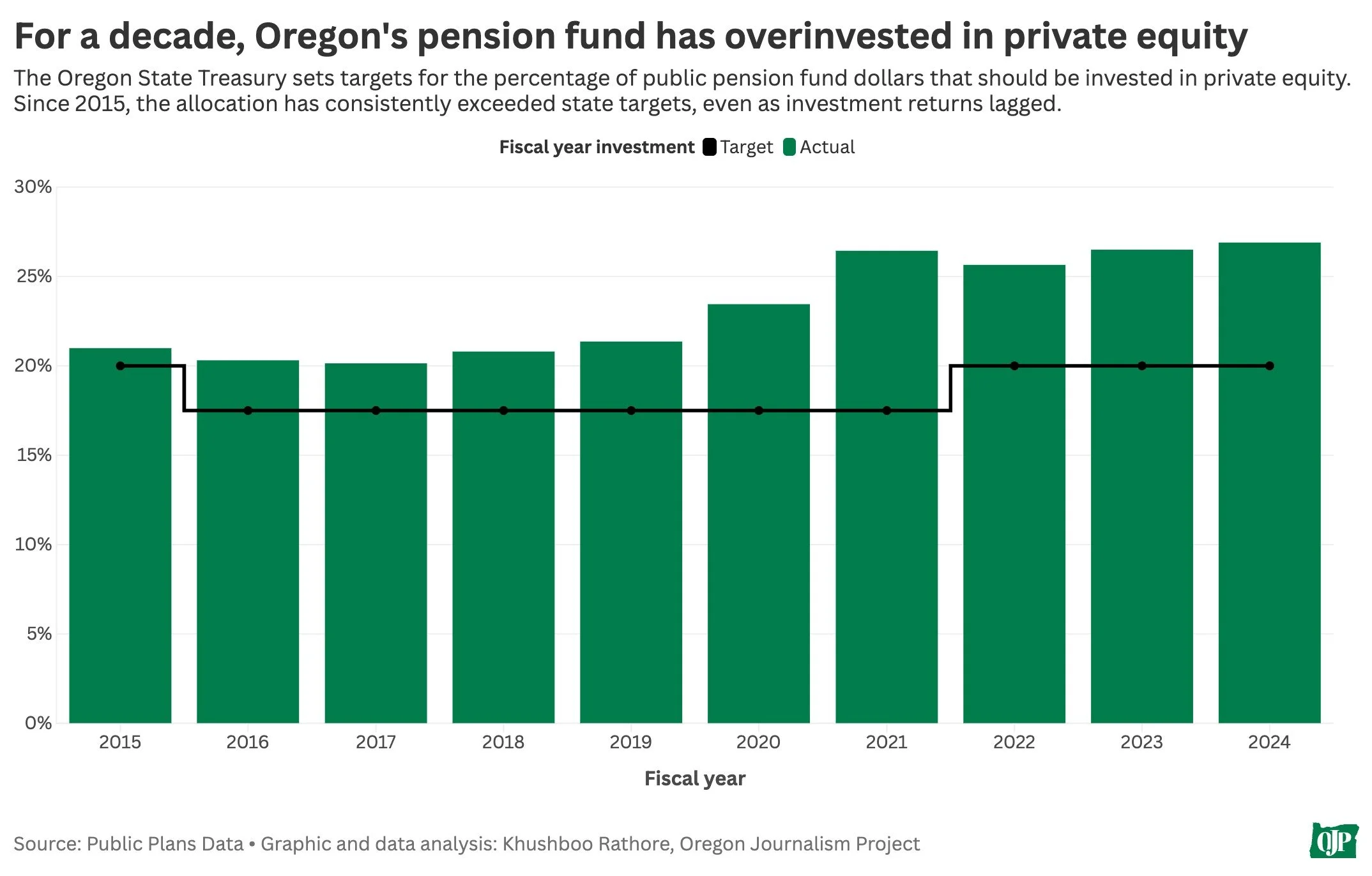

And the stock market has increased in value significantly more than private equity over the past few years (see graph). In other words, OPERF has loaded up on losers and underinvested in winners. As for the private equity investments, they underperformed their benchmarks every year but one over the past decade.

A number of leading pension funds have been moving away from private equity. Last year, the $202 billion Teachers Retirement System of Texas cut its private equity target to 12%, down from 14%. The $41 billion endowment at Yale University quietly decided in April to sell $6 billion in private equity because the funds weren’t delivering the outsized returns that Yale had expected. The sale is particularly significant because Yale pioneered private equity investing among university endowments and many others followed its lead.

If the PERS fund had roughly matched the targets that the consultants and OIC members had committed to stocks and private equity, the fund would have earned about $1.4 billion more in 2024. School districts like Grant County’s and cash-strapped cities such as Roseburg, Lakeview and Coos Bay would have millions of dollars more to spend on teachers, librarians, firefighters, street maintenance workers and other needed services.

Asked for his reaction to the OJP calculation about the $1.4 billion cost of being out of compliance with its 2024 targets, the state treasurer from 2017 to 2025, Tobias Read, replied:

“What is my reaction to not having a crystal ball that tells you what exactly will happen in markets next year? Or 10 years? If we could buy one of those, I’m sure we would have.”

Even current State Treasurer Elizabeth Steiner says changing course is ill-advised. “At Treasury, we invest the $101 billion in the PERS fund based on long-term goals and strategies,” Steiner said. “We don’t chase one-year market ups and downs.” In fact, Kim’s team plans to add to its private equity holdings this year by buying about $2 billion more of the underperforming asset class. Steiner supports that decision.

There are several possible reasons Treasurer Steiner, Kim and others are sticking with Oregon’s private equity strategy.

First, Oregon has a long history with private equity. In 1978, it became the first public pension fund to invest in the complicated asset, with $10 million in a fledgling firm called Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co, which went on to become a giant in the private equity field. Three years later, the Oregon pension fund made a colossal $178 million bet on a $420 million leveraged buyout of Portland’s Fred Meyer grocery chain. The gamble paid returns up to a reported 400% years later.

“When I was there, we were really proud of being pioneers in that realm,” says Mark Gardiner, a Portland businessman who served on the OIC from 1999 to 2007.

Second, Oregon dug itself a big hole in the 1990s by promising generous benefits to public employees that it couldn’t afford. By 2005, it had crawled out of that hole and the system was fully funded, meaning it had enough money in the fund to pay 100% of future liabilities.

But the Great Recession and the accompanying real estate and stock market crash dug a deep new hole. Today, the fund has a $24 billion unfunded liability. Put another way, it has only 77 cents for every dollar it owes to current and future pensioners.

So, like a gambler on a losing streak, treasury staff is making risky bets to try to earn excess returns and reduce the unfunded liability, a phenomenon that studies have noted with underfunded pensions.

A third reason is a culture in which the staff investment professionals believe they know best.

Gardiner, a former chief financial officer for the city of Portland, described a culture in which treasury staff, rather than the appointed council, controlled the agenda.

“The staff and the consultants were always ready to tell you why you couldn't do what you wanted to do,” he says. “Yeah, there was always the ‘Oh my God, we have to get into this fund.’…If you went back, you'd find situations where we bitched and moaned about it and still voted for it. Sadly, there was a go-along, get-along thing there.”

Rukaiyah Adams was chair of the OIC from 2017 to 2020. When she took over, Adams, then chief investment officer at Meyer Memorial Trust, wrote a letter to newly elected State Treasurer Read and the investment council about the risks of too much exposure to private equity.

Industry experts suggested private equity performance was trending downward, she wrote.

“It’s not clear whether our historic commitment to private equity will continue to realize a return premium relative to simpler, less costly and more liquid public market alternatives.”

At the time, the OIC’s target for private equity was 17.5%, but in reality the fund was overweight at 20%. The national average was just 8.5%.

During Adams’ term, private equity as a percentage of the pension fund grew further (see graph).

“Managing asset allocation for a fund as large as OPERF is like steering an aircraft carrier — it’s hard to change direction or pivot suddenly,” Adams says today.

By 2022, under OIC’s current chairwoman, Cara Samples of Fulcrum Wealth Management Group, private equity reached 26% of the pension fund and the OIC had raised the private equity target to 20%.

At the OIC’s Nov. 2 meeting that year, Kim’s staff, along with consultant Meketa, proposed bumping up the target yet again, to 22.5%.

Samples opposed it: Raising the target “to solve the problem of being overallocated, I don’t think we need to do that.”

Later in the meeting, Michael Langdon, then the treasury’s director of private markets, dismissed such concerns: “I could tell you candidly whether it’s 20 or 22 it makes no difference to us. We’re still going to be executing the same plan.”

Samples declined OJP’s requests for comment.

At the OIC’s Jan. 25, 2023, meeting, the overallotment in private equity came up yet again. CIO Kim told Samples: “I don’t think we as an organization are in a rush to get down to 20%. We hope to get there in time, but…we don’t want to lose the long-term value of what we’re doing in order to get to some 20% artificial number.”

If staff considers the treasury’s own targets artificial, why even have an allocation plan, asks Divest Oregon’s Pope.

“This is a case where the staff just didn’t follow the policies set down by the people they're supposed to obey. And it’s a case where the policymakers did not, for whatever reason, ride herd on the staff until it looked like the wheels were starting to come off this vehicle.”

In rebuttal, Read says he and OIC members talked several times about getting private equity down to its 20% target and that, in October 2024, “the OIC was presented with reduction scenarios that would get the fund to those targets in the next three to four years.”

Ten months later, that plan has yet to come up for a vote.

Treasurer Elizabeth Steiner approves of further investment in private equity. (Credit: Brian Brose)

Former State Treasurer Tobias Read wasn’t interested in Monday-morning quarterbacking the state’s portfolio selections. (Credit: Brian Brose)

As chair of the Oregon Investment Council, Rukaiyah Adams warned of too much exposure to private equity. (Credit: Sam Gehrke)

Back in John Day, Superintendent Witty held out some hope for his school district’s fortunes even though the town’s only surviving lumber mill had been shuttered months earlier. An interested buyer had surfaced, and talks among the state and the feds about $8 million needed to upgrade the mill and rescue its 70 good jobs seemed promising.

But, he recently said, he learned plans had fallen through. That meant that over the next school year or two, the Grant County district would lose perhaps as many as 30 students. Even worse, he expects another 6% increase in PERS costs on top of the lost per-pupil funding.

“That would be another $850,000 to $950,000 for PERS again,” Witty says.

And more job cuts, thanks in part to an underperforming pension fund.